This is some classic literature, man. I need to read it every so often just to keep me grounded. It’s been a slow reading year and I really got bogged down on this. Not because of the content or anything, just because I’m kind of busy and distracted.

Tag: literature

I have a friend who used to own a bookstore, the guy has read everything. So I’m wandering through Open Books with him and he’s casually remarking on books he’s read and he mentions something about Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim that makes me want to read it.

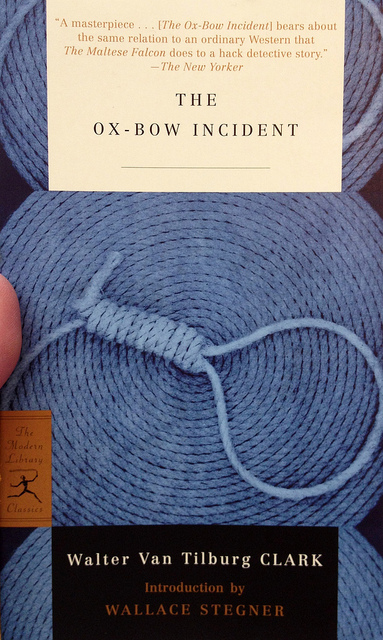

The Ox-Bow Incident

I finished the last two chapters of this book on a plane coming back from Charlotte on a business trip. The flight was half empty and I was seated behind two drunk guys on their way to a bachelor party in Chicago. As I was sitting there in quiet contemplation, the guys in front of me engaged in a long and sometimes animated discussion about Trayvon Martin, Robert Zimmerman, and vigilante justice.

It was a strange confluence of events that forced me to think harder about this book.

If you’re not familiar with the story, you need to know right off the bat that this is generally regarded as the greatest Western novel ever. As a kid, I read a lot of Westerns, so this reading experience really hit home for me. It’s an incredible read and very appropriate for current times.

** PLOT KILLERS FOLLOW **

The story takes place over about 48 hours in 1885 and chronicles a doomed hunt for three murderers by a 28-person posse from a small cowtown in Nevada. It’s told from the perspective of a cowboy in the posse named Art Croft, a sensitive and thoughtful person but a man ill-equipped for the deed at hand. He’s a perfect vehicle to tell the story.

It’s a short book, maybe 240 pages depending on the format. It’s broken down into five longer-than-average chapters. They aren’t titled, but if they were, I’d title them like this:

- The Saloon

- The Posse

- The Hunt

- The Hanging

- The Saloon Again

I read it over the course of a week in four sessions, the last two chapters being a single session. You’d have to be one heartless human to stop after Chapter Four, or just someone with serious time constraints.

This book points out the the evils and perils of the mob mentality and vigilante justice, but it goes deeper. One of the subtler topics Walter Van Tillburg Clark explores is the moral implication of doing the right thing. I’ll use a scene in the book to clarify so you don’t think I’m full of $^|+.

During formation of the posse, the ensuing hunt, and the hanging, there was one man who campaigned tirelessly to cease the charade of justice and bring the suspects back to town to be tried. His name was Davies and he was the local shopkeeper. Davies did everything he could; he got the local judge out of his office to try and stop the posse from going out, he confronted the leader of the posse and tried to reason with him, and he begged other posse members to see his point of view to try and build consensus for stopping the hangings.

Nothing worked. Three men were hanged and their innocence was discovered only moments later on the way back to town.

The aftermath is ugly. The son of the leader of the posse hangs himself when he gets back to town. His father, Tetley, commits suicide by impaling himself on his own sword shortly after hearing of his son’s death. A local rancher promises to take care of the widow and children of one of the hanged.

The reader, I think, finds these pretty meaningless. I still had a sickening feeling for the injustice done to the suspects because it could not be undone. Davies has the same feeling, but he also has a more complicated set of emotions. He feels a tremendous, crushing guilt in his cowardice.

What? Croft, the narrator, is incredulous and tries to talk Davies down from this. Croft expresses that Davies was the only one talking sense and the only one standing up to the leader Tetley, he should feel anything but guilt because he did all he could.

Davies doesn’t feel the same way. He knew the suspects were innocent. He just knew. He also knew that only way he could stop the hanging was to kill the leader Tetley. His guilt resulted from the feeling of relief he felt for not bringing his gun. He was relieved that he didn’t have to make the hard decision to do the only thing that could have saved three innocent men, kill Tetley.

“Yes, you see now, don’t you?” he said in a low voice. “I had everything, justice, pity, even the backing – and I knew it – and I let those three men hang because I was afraid. The lowest kind of virtue, the quality dogs have when they need it, the only thing Tetley had, guts, plain guts, and I didn’t have it.”

…

“All a great, cowardly lie,” he [Davies] said violently. “All pose; empty, gutless pretense. All the time the truth was I didn’t take a gun because I didn’t want it to come down to a showdown. The weakness that was in me all the time set up my sniveling little defense. I didn’t even expect to save those men. The most I hoped was that something would do it for me.” (pg 234)

Wow man, this blew me away. It was an ultra intense scene in the book and it reminded me immediately of the feeling I had after reading the Pat Tillman book. This feeling that some people just hold themselves to a higher standard.

I felt like Davies was a hero but Tillman, like Davies himself, would probably feel differently. Would Tillman have been the type of guy to stand in front of the unjustly accused with a gun and kill anyone who tried to hang them?

This prompted me to re-read my take on the Tillman book and it just led to more questions about my (our) place in this world. How do I guarantee an appropriate response in times of crisis and conflict, especially when faced with crushing peer pressure? When do you step in and when do you walk away? When do you act on what you really feel? When is it right to decide to take a human life?

Tough questions.

This issue was foreshadowed very early in the book but I wasn’t able to connect it until I reviewed things. As the posse was developing Davies tried to nip things in the bud by first reasoning with the group. He even seemed to think one person standing up to them in a non-violent manner would keep them from going. Croft didn’t think so and noted this:

I wasn’t so sure of that. Most men are more afraid of being thought cowards than of anything else, and a lot more afraid of being thought physical cowards than moral ones. There are a lot of loud arguments to cover moral cowardice, but even an animal will know if you’re scared. If rarity is worth, then moral courage is a lot higher quality than physical courage; but, excepting diamonds and hard cash, there aren’t many who take to anything because of its rarity. Just the other way. Davies was resisting something that had immediacy and a strong animal grip, with something remote and mistrusted. He’d have to make his argument look common sense and hardy, or else humorous, and I wasn’t sure he could do either. If he couldn’t he was going to find it was the small but present “we,” not the big, misty “we,” that shaped men’s deeds, no matter what shaped their explanations. (pg 62)

So maybe my description of Croft as “ill-equipped” earlier was wrong and maybe Davies was even less-equipped to stop this charade of justice. Maybe only someone who could apply the “big, misty” morality to the here-and-now in the face of physical opposition could stop this thing. If Croft had this insight, why didn’t he take the action? Or, maybe worse, why didn’t he feel the same guilt that Davies felt? Is Davies just irrational and too hard on himself?

Food for thought.

This book is especially appealing to fans of the Western. It has many of the stereotypical western characters but does not have many of the stereotypical western scenes. There was no big shootout at a pre-arranged place and no hero swooping in to save the day with guns blazing. But there was a big woman called Ma who can fight like a man and a Civil war vet who still doesn’t think the war is over.

I’ve thought about this book a lot over the last 48 hours. I need to make a point to come back to it in a few weeks.

A Visit from the Goon Squad

This book kept rolling up on award lists and I thought it sounded kind of cool. Additionally, I needed some literature to round out the year, so I grabbed it. Yep, it’s lit. It won a few best book awards, including the Pulitzer. WAIT, don’t click on that yet! Watch the interview in the link after. That’s what I did. It’s better because there are some spoilers.

Trust me on this waiting thing; when things came together in the middle of the book, you want it to feel like something clicked, like something genuine.

** PLOT KILLERS FOLLOW **

It’s a set of short stories that are loosely linked. Each story takes the perspective of one of an extended group of friends and acquaintances who are mostly connected, in some manner, to either Bennie or Sasha. The stories aren’t chronological and they don’t have any introductions. They do have somewhat of flow, and they all have some connection to the music industry, so you at least have something to hang your hat on.

Just be warned, this is not a standard novel. It’s not linear. I didn’t know that going in and I’m not sure if that made it more exciting or not. It certainly made it more mysterious and confusing until about the middle of the book.

At around half way, in a pivotal and highly memorable scene, the goon angle slaps you in the face. At this point things crystallize and this becomes a very meaningful book. It’s a memorable scene and still sticks in my mind for so many reasons. In it aging rocker Bosco plots his Suicide Tour and says, “Time’s a goon, right? Isn’t that the expression?”

I’ve never heard this expression. But as soon as I heard it something clicked: big theme of this book is the passage of time.

That Bosco story I just mentioned happens in the middle. Then, near the end, in a Powerpoint presentation by the daughter of the assistant (Sasha) of the record executive (Bennie) who’s wife Bosco was speaking to while her ex-con, writer brother (Jules Jones) nods in approval at the idea of a Suicide Tour (he wants to get the story), you find out this:

Conduit: A Rock-and-Roll Suicide by Jules Jones

Mom bought the book, but she never mentions it.

It’s about a rock star who wants to die onstage, but ends up recovering and owning a dairy farm.

There’s a picture of mom on page 128.

Yep, that’s how this book unfolds. It just skips forward or backward, depending on whatever. You have to draw the connections yourself and letting them reveal themselves is most of the fun. And yeah, that snippet above is actually in Powerpoint form. It’s chapter 12. The whole chapter is a Powerpoint presentation. Genius. It may be one of the coolest chapters in a book I’ve ever read – I was dumbstruck, moved, blown away, saddened, enlightened, overjoyed. It was a stack of Powerpoint slides. Seriously.

And to think, Jennifer Egan had never even used Powepoint until this chapter, which she added after the publisher agreed to publish it. Great stuff.

Read the book. Read this post. Watch the interview, in that order.

The Sportswriter

Up until this point, I haven’t read any so-called literature this year. When I say lit, I’m not necessarily talking about the classics or anything. I’m just talking about fiction that is a little more serious and thoughtful than my normal crime and thriller reading. Page through the stuff I’ve called lit and you’ll get an idea.

I’m classifying The Sportswriter, the first book of this Richard Ford trilogy, as literature. It’s the story of a guy named Frank Bascombe, a 39 year old sportswriter and divorced father living in Haddam, New Jersey. It’s set during Easter Week (back in the 1980s I’m guessing), and follows Frank around for a few days as he interacts with his ex-wife, his girlfriend, his family, his girlfriend’s family, and his other divorced friends.

Some crazy, shocking stuff happens and some boring, plodding stuff happens. Kind of like real life. This book exhibits a feature I find in so-called literature: the capacity to either really bore me or really surprise me, both in the extreme. It also contained some family carnage, another feature of literature which I find comforting, for some warped reason.

It has a somewhat somber, melancholic tone. Frank just kind of bounces around and never gets too riled up about anything. Early on, he gives this pearl of wisdom to set the scene for the book.

… For now let me say only this: if sportswriting teaches you anything, and there is much truth to it as well as plenty of lies, it is that for your life to be worth anything you must sooner or later face the possibility of terrible, searing regret. Though you must also manage to avoid it or your life will be ruined.

He seems to be saying, I think, that it’s a delicate balance. You must go out on a limb far enough only to face the possibility of regret, yet manage to avoid it. I struggle to tell if Frank has achieved this in his life. He’s a difficult guy to figure out and it got frustrating at times. There are long sections of him just batting things around in his head so there’s plenty of material to sort through.

His recollections are strange and the situations he gets into are bizarre, but they lay the groundwork for a constant state of wonderment. As I read, I kept saying to myself, “Wow, where did that come from?” Then there are moments of clarity amongst the chaos. He certainly set himself up for the possibility for regret, and I think he has avoided it, despite some significant hardship.

He laments things, for sure, but not regret. For instance, he seems to have been an early lamenter of the trend towards stats-minded sports leadership (remember, this book was written in the 1980s):

… When sports stops being a matter for speculation, even idle, aimless, misinformed speculation, something’s gone haywire – no matter what Mutt Greene thinks – and it’ll be time to get out of the business and for the cliometricians and computer whizzes from Price Waterhouse to take over the show.

That’s just a random thought he had, as he was listening to sports talk radio in the car, slowing down to see if his palm reader was available, while on his way to identify his friend, a fellow divorced guy who tried to kiss him a few days ago, who had just committed suicide. I probably could have broken that down into a few sentences, but it wouldn’t have sounded any less weird, so I’m not even going to try. And that only scratched the surface of the oddness.

After sorting through the deluge of thoughts in Frank’s mind, it does make you question the point of sports. I’ve come to terms with my sports obsession recently. For me, it’s not that unhealthy of a hobby and mostly manifests itself in participation (golf and running). Sure, I get deluded at times that some of my self-worth is tied to the success of ND football or my handicap index, but that passes quickly. And I often stare blankly at the TV when golf or the White Sox are on, but that’s healthier than watching reality TV or sitcoms, right? Say yes.

I dug a little deeper and found this essay called Sport and the literary imagination, by this guy named Jeff Hill, which references Frank Bascombe. It speaks to the “illusion” of sports in the minds of men. Here is how Hill puts it:

… He [Bascombe] is a victim of his own illusions, one of a group of flawed men in a novel whose force comes from sensible, purposeful, steely-minded women who set clear goals and then determinedly pursue them, on the whole successfully. Sports provides for Bascombe a romanticized view of the world which he refuses to abandon even when the ideals of sport are undermined by it’s realities (page 105).

That does sound a little like myself. I overly romanticize the hard work and determination put in by athletes in the pursuit of greatness, when in reality these athletes view it as a job – a path to riches and fame (even college athletes). I know this, yet I still get engrossed, which really makes me an idiot, I guess.

Deep stuff. Cool book. There’s a certain familiarity that makes it approachable and interesting. Frank gets into these situations that we’ve all been in (meeting your girlfriend’s parents, struggling with your job, dealing with family on holidays) and just analyzes them to death. It was fascinating to read and fun to reflect on, but I don’t know if I got the point the whole time.

I do feel like this book may have helped me understand some of the great mysteries of life a little better. I also feel like the feeling of wonderment I experienced occasionally during the reading is a satisfying feeling which adds value to my life, much like excitement, anxiety, and surprise do in the popular fiction I read. But some of the subtler points may have been lost on me. I’m certain there was plenty of symbolism that I missed. It doesn’t matter. I liked it.

Generosity: An Enhancement

This was a fine recommendation that I found in the San Francisco Panorama and from the folks at McSweeney’s. Ever since reading a book about books by Nick Hornby (published by McSweeney’s I think), I’ve had good luck with their recommendations or recommendations by their affiliates. This book also appealed to me because the author is a local guy and it takes place in my neighborhood.

Richard Powers has put together a pretty solid career in literature and I didn’t hear about him until I read a San Francisco newspaper. That’s my fault dammit. What kind of Chicagoan am I? Heck, he won a National Book Award in 2006 for The Echo Maker. I should actually be ashamed of myself, but that would give me too much credit (like I pay attention to the art scene around here). Generosity blew me away. It’s my favorite work of fiction so far this year. And plus, I don’t feel one bit guilty classifying it as literature – the guy won a National Book Award dammit.

It’s the story of five people, really, but most of the story revolves around one of the five. She’s Thassa, a twenty three year old film student from Algiers attending a fictional south loop university. Thassa just may have a genetic predisposition for happiness. I wouldn’t say she’s the main character because you get the perspective of the other four characters (mostly as it relates to Thassa) more than you get Thassa’s. The strange thing is that I wasn’t able to tell who was narrating this book until the very end. Confusing at times, but not in a bad way. In fact, it was confusing in more like a childlike wonder kind of way.

Now I’ve finished and I have some feel for the narrator. But we’ll save that for after the Plot Killer warning. Before we get to that, besides the story, I want to talk about why this book was so enjoyable.

First off, I loved the author’s grasp of Chicago. My wife and I live in one of the neighborhoods that the characters often pass through:

The walk from Logan Square to the South Loop takes hours. He’s healthy, and the hike should be effortless. But he’s winded by Bucktown. On foot, Milwaukee Avenue is another country. He knows nothing about the place where he lives. By Wicker Park, he’s overheard six languages. And all the more recent ethnic groups supposedly live on the other side of town.

And the weather, he has it pegged:

Mid-November, the semester’s home stretch, and the city drops into real chill. The sky molds over, and even the two-block walk from the El to the college cracks Russell Stone’s skin. Now the lake effect begins to work against this place, and the vanished autumn is just a tease that he should have known better than to trust.

Chicago is all over this book. Powers just has captured the feel and tone of the city. He takes us through parts of the north side, the south side, and even a little bit of the suburbs. I found myself constantly saying, “Yeah, that’s right.”

Then there is the underlying commentary on our society and the reliance on technology. It’s a relevant topic today and one I find myself thinking about a lot. Stuff like this:

The price of information is falling to zero. You can now have almost all of it, anytime, anywhere, for next to nothing. The great majority of data can’t even be given away.

But meaning is like land: no one is making any more of it. With demand rising and supply stagnant, soon only the dead will be able to afford anything more than the smallest gist.

…

Information may travel at light speed. But meaning spreads at the speed of dark.

Also, there is some great wry comedy. One of the main characters (Russell Stone, who doesn’t own a mobile phone or a car) often seeks advice or counsel from his brother, who really shouldn’t be disseminating it:

He calls Robert, who talks him through the steps of renting a car. His brother is shocked to hear his plans. “Are you sure? Canada, man? It’s a parallel universe up there. The queen on the dollar bills. The guaranteed health care. You are aware of the whole French thing?”

And finally, there is a serious intellectual commentary running throughout the book on science and, more pointedly, on the ethics and issues surrounding the human genome and potential manipulation thereof. It makes you think, a lot.

All this great stuff, and I have hardly touched on the story and the characters.

** PLOT KILLERS FOLLOW **

Powers has created this alternate universe a few years in the future. It’s a time when genetic manipulation of embryos is commonplace to insure that children don’t have diseases and such. His universe includes a famous Irish talk show host in Chicago named Oona and popular science TV show called Over the Limit, hosted by one of the main characters. As you can guess, science and the general public are highly interested in this happy woman’s genes. The story is about how the four other main characters deal with the discovery of Thassa’s genetic gift of happiness when it becomes public. Those four people are two of her closest confidantes (teacher Russell Stone and psychologist Candace Wells), a famous scientist (Thomas Kurton), and the talk show host (Tonia Schiff).

Sounds strange, maybe, but it’s not. It’s great stuff. It’s humorous and Powers keeps it light but mixes in plenty of thought-provoking, and often satirical, commentary on today’s society.

I was engrossed in the story. So engrossed, that I never stepped back and thought about how it was structured. I feel like a dumbass, but it really never hit me that the story teller was one of the characters in the story, until the last few pages that is. I felt a little cheated, but not really. The bottom line is, dammit, that I missed this piece of foreshadowing about a quarter of the way through:

Forgive one more massive jump cut. This next frame doesn’t start until two years on. It’s the simplest of predictions to make. Tonia Schiff will find herself on a warehouse-sized plane flying east above the Arctic Circle, unsure what she is hoping to come across at the end of the ride.

I was confused because the book jumps around sometimes, so this plane flight would have made more sense had I noticed that it was two years in the future. Sometimes I wonder how I get through books and enjoy them. I feel like I missed out on a whole bit of magic. It’s like I need to get better at reading. Can I really enjoy reading as much as I think I do when I make rookie mistakes like overlooking key foreshadowing? Answer: Yes! Does a 30 handicapper enjoy golf? Does a runner feel proud after a six hour marathon. Answer: Yes! Enjoyment has nothing to do with skill or ability.

Sorry to go off on a tangent.

It was a great book. I loved the characters. I thought the love story was decent. When I read the reviews on Amazon, Powers seems to take a hit for his character development, but I disagree. Granted, he splits his character development amongst five main characters, so maybe there just isn’t time to tighten every detail. The ensemble worked well for me.

The Name of the Rose

So I’m starting early this year with what I’m going to classify as literature. And yeah, it felt like lit. This was a long, slow read for me but it was rewarding when it was over; not so much because it was exciting or dramatic, but because I feel like I learned a few things.

As I’ve already stated, I’m getting in touch with my inner Catholic this year so this book goes along with that effort. It’s a mystery that takes place in an abbey in Italy that is accused by the Pope of heresy (year 1327). Set against the backdrop of a visit from the Pope’s envoy to assess the heresy are some grisly murders in the abbey. William, a visiting monk from England, arrives at the abbey in advance of the envoy as somewhat of an unbiased interlocutor (did I use that correctly?) but he seems to be sympathetic to the abbey. He also voraciously pursues the evildoer who is committing the murders.

The story is told from the first person perspective of William’s sidekick, a young monk named Adso. It takes place during one of the many upheavals in the church. In this time period, Michael of Cesena is in a serious disagreement with the Pope about how strictly to practice the vow of poverty. Michael believed in the strictest teachings of Saint Francis of Assisi and the Pope viewed this as heretical. Michael is at this abbey during the time, so the book combines some history and fiction.

Interesting stuff to me because this is roughly the same time period as World Without End and gives a little deeper insight into how the church was being affected by forward thinking types who combined science and philosophy with theology, like Sir Roger Bacon and William of Occam. Both of these men were coming at things from a philosophical and scientific perspective that often made the church uncomfortable.

William, the fictional main character, uses logic and science to track down the killer and to try and reason with the inquisitors who seem to be biased against Michael of Cesena and his followers. It was, at times, an exciting mystery and interesting character study. William appears to have the ability to remain faithful to his religion while relying heavily on the scientific method for his daily work. I think this is one of the messages, that science and faith can coexist.

Unfortunately, the book was full of side trips into fantastical dreams and theological discussions that were lost on me. It would have been a much better read had I done my research on the people and times before hand.

Netherland

Obama suggested I read this book. Not directly of course, I actually saw in Newsweek that he was reading it. Usually, if you hear about a government official reading something, it’s some sort of nonfiction. You know, like Lincoln’s biography. But Obama is admitting to reading a work of fiction, which I find interesting, so I grabbed it. Maybe the White House should start a “One Book, One America” project kind of like we do here in Chicago. I would probably partake.

So here is the snippet from the Jon Meacham interview with Obama in the May 25, 2009 edition of Newsweek:

What are you reading? I’m reading this book called Netherland by Joseph O’Neill … It’s about after 9/11, a guy—his family leaves him and he takes up cricket in New York. And it’s fascinating. It’s a wonderful book, although I know nothing about cricket.

And as you divide up your time, when do you steal the time to do that? I’m a night owl. My usual day [is]: I work out in the morning; I get to the office around 9, 8:30 a.m. to 9 a.m.; work till about 6:30 p.m.; have dinner with the family, hang out with the kids and put them to bed about 8:30 p.m. And then I’ll probably read briefing papers or do paperwork or write stuff until about 11:30 p.m., and then I usually have about a half hour to read before I go to bed … about midnight, 12:30 a.m.—sometimes a little later.

Interesting stuff. I’m Newsweek reader. And I agree with Obama, it’s a fascinating book. There are so many cool moments in this book. I want to talk with someone who has read it.

It’s the story of a Dutch guy named Hans, a hotshot London-based economist for a big investment bank who moves to New York in about 2000 with his wife Rachel and young son Jake. They enjoy New York as a family for a couple of years then 9/11 hits and things start to change. Family problems ensue. His wife and son end up moving back to London but Hans stays in New York for a few more years.

He ends up befriending a guy from Trinidad named Chuck Ramkissoon, whom he met playing cricket. Chuck and Hans are both passionate about cricket and the game forms the bedrock of their friendship. They are completely different people in just about every way – race, religion, profession, upbringing, temperament – but they find common ground in this game; a common ground that transcends the field of play. This is a big theme in the book. Here’s a sampling where Hans is reflecting on the pre-match preparations:

Chutney music was playing, and to its relentlessly tinny and cheerful urgings we’d drive off to New Jersey, Philadelphia, Long Island. We sat mostly silently in the van, absorbed into the moodiness that afflicts competitors as they contemplate, or try to put out of their minds, the drama that awaits. What we talked about, when we did talk, was cricket. There was nothing else to discuss. The rest of our lives—jobs, children, wives, worries—peeled away, leaving only this fateful sporting fruit.

I love that passage. These aren’t professionals, these are just weekend warriors, but they are still passionate about the game. It gets deeper as the book progresses. Deeper in that O’Neill starts delving into the subtleties of how this sporting relationship creeps into other parts of our lives, and Hans’ and Chuck’s lives, but never fully hangs around.

The book is much, much bigger than this though.

It’s about New York, the aftermath of 9/11, and American politics, but it doesn’t make proclamations about right and wrong. It does make observations about what New Yorkers were talking about and how some of them felt. This is some of the frustration that Hans felt:

In this ever-shifting, all-enveloping discussion, my orientation was poor. I could not tell where I stood. If pressed to state my position, I would confess the truth: that I had not succeeded in arriving at a position. I lacked necessary powers of perception and certainty and, above all, foresight. The future retained the impenetrable character I had always attributed to it. Would American security be improved or worsened by taking over Iraq? I did not know, because I had no information about the future purposes and capacities of terrorists or, for that matter, American administrations; and even if I were to have such information, I could still not hope to know how things would turn out. Did I know if the death and pain caused by a war in Iraq would or would not exceed the miseries that might likely flow from leaving Saddam Hussein in power? No. Could I say whether the right to autonomy of the Iraqi people—a problematic national entity, by all accounts—would be enhanced or diminished by an American regime change? I could not. Did Iraq have weapons of mass destruction that posed a real threat? I had no idea; and to be truthful, and to touch on my real difficulty, I had little interest. I didn’t really care.

In short, I was a political-ethical idiot. Normally, this deficiency might have been inconsequential, but these were abnormal times.

This is typical Hans; highly successful, but somewhat insecure, and really more concerned about getting through his day rather than dwelling on issues like this. I wonder if many New Yorkers felt like this. O’Neill is a New Yorker, so he must be basing this on something.

** PLOT KILLERS FOLLOW **

It’s also about marriage and how it changes with time and circumstances. Hans’ and Rachel’s marriage unravels with 9/11, but not because of 9/11. But they don’t get divorced and it eventually revives. The psychological wrangling that Hans goes through surrounding Rachel is a big part of the book. He perseveres through the arguments, the affairs, and the ocean.

The arguments often center on America and the reaction to 9/11. Rachel spews out acidic tirades against George Bush and Hans doesn’t get why she’s all wound up. Hans, I think, loves New York. Hans and Rachel eventually find some middle ground. There’s a great scene late in the book where Rachel has to weigh her feelings for America against her feelings for Hans. It occurs at a dinner party in London where one of their British friends, Matt, refers to 9/11 as “not a big deal.” Hans disagrees strongly and the others seem to be on his side, but much snickering amongst this small group of Brits makes it clear that they find his views laughable. The following ensues, told in first person by Hans:

For some reason, I’m filled with rage.

I lean over to Rachel. I gesture with my eyes, Let’s go.

Rachel has not followed what has happened. She looks surprised when I stand up and put on my jacket. It’s a surprise for all, since we have not finished our roast chicken.

“Come on, Hans, sit down,” Matt says.“Rachel, talk to him.”

Rachel looks at her old friend and then at me. She stands up. “Oh, piss off, Matt,” she says, and waves good-bye to everyone. It is quite a shocking moment, in the scheme of things, and of course exhilarating. When we step out together into the wet street, holding hands, there is a tang of glory in the air.

Cool stuff. Watching their evolving relationship is a great part of this book.

O’Neill also incorporates some contemporary cultural references that I was surprised by, but maybe I just haven’t read enough contemporary lit to know any better. There is a scene where a gangster, named Abelsky, is roughing up someone and he actually makes a cup of coffee in the home of the guy he’s beating up. This ensues:

“You got NutraSweet?” Abelsky repeated. The man said nothing. Abelsky took a mouthful of coffee then spat it back into the cup. “Without NutraSweet, it tastes like shit,” he said. He put the coffee down on the leather desktop. “That OK there? I don’t wanna make a ring.”

I had to laugh, for various reasons.

And O’Neill incorporates Google Maps into the mix a couple of times. Chuck is a gangster and eventually gets murdered sometime after Hans returns to London to reunite with his wife and son. Hans still remembers his pal and one night Hans pulls up Google Maps to locate the cricket field that he was helping Chuck to build:

I veer away into Brooklyn, over houses, parks, graveyards, and halt at olive-green coastal water. I track the shore. Gravesend and Gerritsen slide by, and there is Floyd Bennett Field’s geometric sprawl of runways. I fall again, as low as I can. There’s Chuck’s field. It is brown—the grass has burned—but it is still there.

I found these methods effective and engaging, they make the book timely and approachable. What makes an author bring this stuff up and throw it into the mix? Is O’Neill just a heavy user of NutraSweet so he thought it might be cool to throw it in? He could have said “the blue stuff” or “Equal.”

I really enjoyed it. It’s a relevant character study and it’s about the world we live in now. It’s a great book and moved me more than anything else so far in 2009.

The Paperboy

I’m not sure how I came about this book. I think my wife, Gail, picked it up at a library book sale knowing that I had already enjoyed Train. She may have remembered that Dexter was famous for his book Paris Trout. Or maybe she just knows me. I don’t think she’s read any books by Pete Dexter and I don’t think I’ll be able to convince her to do so.

Why? Well, I just don’t think Gail has the same fascination that I do with family carnage. I use the term carnage loosely. I don’t mean that I enjoy stories about killing families. I use the term to describe stories about breakdowns in familial relationships that are often more painful than death because they are so insidious.

For some reason, in my estimation, this makes for a good story. I can’t explain it. What’s enjoyable about a family breaking down? I don’t know. Maybe it isn’t enjoyable. This could be the wrong word to use. Maybe engrossing is a better word to describe my involvement with books like this. Or maybe I should say I’m engaged; that may better describe it.

I remember it starting in college when I read Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf in a lit class. I was amazed by it. Then I saw the play about a decade ago and I was blown away. The acidity and enmity of these two people towards each other was mesmerizing. So now, a few times a year, I engage in some carnage. The Paperboy was certainly along these same lines, although a little less so and therefore much more readable then the other books I’ve labeled as such.

The word paperboy in this book, I think, could refer either collectively to the four male protagonists or individually to the narrator, Jack James. Jack is the youngest son of a local newspaper scion in a rural Florida town. Jack is kind of a screw-up, but a good kid; he drives one of the delivery trucks for his dad. Contrast this to Jack’s brother Ward, who is one half of a famous investigative reporting duo for the Miami Times, the other half being a gentlemen named Yardley Acheman.

Bothers Jack and Ward are brought together when Ward and Yardley make a visit to the small town where Jack lives with his dad. They are there to investigate the murder of the local sheriff and the subsequent conviction of the perpetrator. Jack is hired as their driver and errand boy. The dysfunction occurs within the Ward family, between the distant dad and the two son’s. Therein lies the soul of this story, but there’s a lot more that makes this story great.

** SPOILER ALERT **

As the relationship with their father grows more distant and the complications in the investigation become greater, the brother’s relationship solidifies and grows. It’s a beautiful thing to see and provides a hopeful backdrop.

If this family relationship is the soul of the story, then the heart of the story is the daily recounting of the paperboy’s search for the facts in the murder of the local sheriff. To me, it’s even more timely and interesting because it’s a discussion of the morality, ethics, and value of investigative journalism, a pursuit that is under fire now more than ever as the newspaper industry continues its decline. I come across articles daily, asking where we, as a society, are going to get this style of reporting if all of the newspapers go bankrupt.

Dexter takes this topic to its endgame. The paperboy’s investigation leads to a story, the story leads to a Pulitzer for Ward and Yardley, then the Pulitzer leads to an investigation of the original story by a rival Miami paper. Ironic, because the investigative reporter for the rival paper once worked for the Miami Times. In fact, she idolized Yardley before he made a mockery of her by pushing her into a pool in front of all the bigwigs at the newspaper’s celebration of the Pulitzer. It’s a great twist.

And I don’t use the word twist loosely. Dexter’s writing contains a host of twisted characters who do some twisted things in some damn twisted scenes, usually involving violence and sex. It’s dark, so you have to like a little darkness to embrace Dexter. But it’s that darkness that makes the relationship between the brothers that much brighter.

Great book, which I’m classifying as lit because I want to. I don’t think it fits into popular fiction.

Then We Came to the End

This whole office life is hell theme has played out for a few decades now. My earliest memories are from the late 1980s and Dilbert. Even as a college kid I found Dilbert kind of funny despite my lack of experience in a corporate environment. Fast forward more than a decade to the UK version of the office. Now that was pretty damn funny stuff. Side splitting funny actually. Around the same time came the American movie Office Space. Awesome, I loved it – that scene where they destroy the printer with gangsta rap in the background is one of the greatest scenes ever in American film. Then we had the US version of the office, which hooked me early on. However, about half way through the second season I got bored with it and quit watching.

Was I just jaded by the office life is hell genre? Actually, this occurred at a point when I quit watching just about all comedic, reality, or dramatic TV, so maybe there were larger forces at work. Whatever the case, I wasn’t going to pass up Then We Came to the End, despite its linkage to the office life is hell genre and my apparent discouragement with it. Heck, it was getting killer reviews everywhere and the NYT called it one of the top 10 books of 2007. So here we are. It’s a day after finishing it and despite struggling early on, I ended up liking it.

It’s a story about a Chicago advertising firm set during the tech bust. Cushy marketing jobs at the Michigan Avenue based firm are being trimmed and the best way for the employees to deal with the stress (and lack of work) is to gossip, play jokes, and complain. There is a host of kooky characters and the situations they get themselves into are described in great detail by Ferris. The weird and humorous stuff Ferris comes up with is very creative and the depths in which he describes them is amazing, but early on it feels like recycled office life is hell material.

Eventually though, there are strong moments and solid themes that raise this book above the standard material out there today, which invariably degrades into making fun of the stupid boss and casting all consultants as evil beasts. Ferris goes beyond this tired act.

** PLOT KILLERS FOLLOW **

The interlude (I didn’t come up with that term) about Lynn Mason (the boss) and her last night before surgery to remove a cancerous tumor is well done. Ferris changes the perspective and the chapter title styling and just launches into it. I really couldn’t tell what was going on, but I couldn’t put it down. It held my attention well. And the way Ferris linked up this interlude with the rest of the book was smooth, really smooth. The interlude was actually a book written by one of the characters, a reading of which brings the whole crew together at the end. Great stuff.

The other memorable scene occurred when Joe (the #2 guy) tells the story of his trip to jail to visit Tom Mota (the office villain who everyone feared would one day come back to blow away the floor after being let go). Joe fired Tom. Not because Tom wrote FAG on Joe’s wall (nobody was really sure who did this). Nope, Joe fired Tom because they were cutting back. Tom, in turn, hated Joe, but not really. Tom just hated being at the firm. To make a long story short, it turns out that Tom figures out that he admires Joe for staying above it all. You had to be there, but it’s a great scene. The last thing that Tom says to Joe before he is taken back to his cell is:

“Yeah.” Tom raised his manacled hands abruptly. “Stay up here, you f&%#,” he said.

Good stuff. All in all, it was a labor at times, but worth the read.

One more thing, Ferris has Chicago down pat. He knows about the long lines at Potbelly, the weather, the neighborhoods, the suburbs, the lake … you name it. If you live in Chicago, it will all be very familiar to you.