This is a little book that packs a big motivational and inspirational wallop. Leonard is an ex-military guy and writer for Esquire who took up aikido late in life (age 47). He uses his exploration of aikido as the basis for this book, but his thoughts and theories can be applied to any pursuit. I got a lot of out it.

When you’re reading a book in the middle of a series, you know the hero isn’t going to die. This takes away some of the anxiety you feel when the hero embarks on the “attack on the fortress,” against impossible odds of course. Which is not a good thing because it also takes away some of the excitement of the book. However, series writers usually align their main characters with friends, family, cohorts, and colleagues who fall in harm’s way, thereby putting someone you care about in peril, which restores some of the excitement.

Child is expert at this. He often has Reacher finishing up the book with an “attack on the fortress” and Reacher rarely goes in alone. He’s usually accompanied by at least one highly attractive female and one person with some military or law enforcement experience. It’s always pretty implausible, but who cares. I don’t care how formulaic Child gets with this stuff, he always manages to throw in enough twists and coolness that each book seems fresh and fun.

My wife and I differ on our fiction choices; my tastes are more accepting of a slower paced mystery-style thriller, whereas Gail prefers something that runs at breakneck speed. However, we meet at Lee Child and both like the series. They’re good stories and Reacher, the main character, is outrageous. Who can’t love a guy who lives completely off the grid and only travels with the clothes on his back (which he replaces occasionally and washes almost nightly)?

Chock up another great one. The popular fiction I’ve read this year has been great. Shortly I’m going to sit down and review my year in books. Maybe I’ll do that on Christmas Day, seems like a great Christmas Day kind of thing to do.

P is for Peril

I’m getting close to catching up with Grafton’s alphabet mystery things. They’re just frickin’ reliable and I can bank on some great fun. I would love to know how Grafton feels about her predecessors like Raymond Chandler. In certain ways she pays homage by creating a hard-boiled, lonesome, private detective embroiled in smartly woven crime novels that highlight greed, corruption, and other human frailties. But she also pokes fun a little and makes things lighter. This book made me think of some similarities and differences.

One method to deepen the persona of said private detective is to build a relationship with coffee, cigarettes, or some other sort of vice. For example, in The Long Goodbye Chandler often had Marlowe making coffee. Real good coffee. I seem to recall rich descriptions of a simple cup and it was easy for me to picture Marlowe hunched over a cup of coffee, reading the LA Times, sorting through the next steps in solving whatever mystery was unfolding.

In much the same way, Grafton has Millhone eating McDonald’s all the time. Junk food, it’s another vice. But it allows Grafton to throw in some humor. Early on, Millhone has this run-in with breakfast.

I stopped off at McDonald’s and ordered coffee and a couple of Egg McMuffins. I needed the comfort of junk food as well as the nourishment, if that’s what you want to call it. I munched while I drove, eating with such eagerness I bit my own index finger.

It’s easy to picture a Millhone eating in her car while she’s ruminating on the details of the case. Grafton’s methods always keep it a little lighter, but I think it’s just as effective for character development and it strikes the right chords with me for the most part. I don’t think Millhone is supposed to be as dark as Marlowe, and she isn’t.

But both Millhone and Marlowe are alike in that both of them shun the societal norms of marriage, kids, and settling down. Recall that passage I talked about where Marlowe goes on a tirade against any other life but the one he is living. Take a read, I excerpted it in The Long Goodbye post. Millhone has a moment kind of like that when she goes to interview someone for her case. She’s interviewing a woman at the woman’s home, where there’s a handful of screaming, rambunctious kids. The screaming is so loud that Millhone can’t concentrate on the conversation. She thinks:

I tried to concentrate on what Blanche was saying, but all I could think about was that even at my age, a tubal ligation probably wasn’t out of the question.

So, much like Chandler, Grafton crafts Millhone in a manner that you never have to worry about her giving up this detective thing. Maybe we’re wrong though, who knows, maybe at “Z,” Millhone will have a husband and a kid and just ride off into the sunset. Something to look forward to I guess. That would certainly close out Millhone.

Hillerman died a few months ago and I feel like he never closed out his characters. But I may be wrong because I didn’t read the last few with that thought in mind because I didn’t realize how close to death he was. I’ll reread them all when I retire.

The Omnivore’s Dilemma

Endlessly fascinating! I know, it sounds cliché, but it accurately describes this read. Every time I sat down to read it, I was engaged, tuned in, and thinking about my relationship with food (a relationship that is somewhat warped). I think that’s what Pollan is trying to do here, just give you information so you can think about what ties you and your food together. He nails it big time and although I’m not going to make any major changes in my eating habits immediately, I have a feeling that this book will stick in my mind forever and certainly change how I view what I shovel into my gullet.

Warning, this is an aside! Before I launch into my take on this book, I need to mention something about really great nonfiction and really great fiction. I’m never as captivated by really great nonfiction as I am by really great fiction. This book still took me a few weeks to read and it’s one of the best chunks of nonfiction I’ve read in years. Contrast this to a little piece of Scalzi’s sci-fi that I read while I was reading this book; I banged through it in a matter of days. I just get along a little better with fiction, I guess.

Pollan structures this book as a description of four meals that he consumes with family and friends. He uses each meal as a mechanism to describe four different ways that food can get to your plate. He digs deep, and goes way back to the original speck of energy that indirectly caused the origination of that morsel of food you’re going to put in your mouth. In the process, he goes on numerous thoughtful and often humorous diatribes about various social and ethical consequences of eating what we eat. It’s not preaching at all, it’s just discussing. I think he does a good job of looking at things from multiple angles.

The four meals in order are:

- Industrial (burgers, fries, and McNuggets in the car on a California expressway, with wife and son)

- Organic Industrial (oven roasted chicken and vegetables, steamed asparagus, organic ice cream and organic blackberries, all purchased from Whole Foods, with wife and son)

- Grass Fed (grill roasted chicken and sweet corn, chocolate souffle, from Polyface Farm in Virginia, with friends)

- Perfect Meal (wild California pig, slain by Pollan himself, hand picked greens, Bing cherry cake, with fellow hunters and gatherers and wife and son)

Think of these meals as a continuum – a continuum from most processed (McDonald’s) to least processed (wild pig), from higher on the food chain to lower, and from industrial to private. Do not interpret this order as going from unhealthy to healthy, unsustainable to sustainable, or ethically wrong to ethically virtuous. However, I wouldn’t be surprised if many interpret it this way. Pollan, at times, may come off as self-righteous with an agenda, but I think he tempers it with a grasp of reality. I read it with an open mind and I haven’t checked any of his facts. I assume they are mostly correct because this book hasn’t been met with any noticeable public outcry from, say, the beef industry or McDonald’s. But like any work of nonfiction, or news story, read it with skepticism.

So on to the four meals. The basis for the industrial meal is corn, and Pollan explores it in detail in the first quarter of the book. I knew I was going to like this book when I came across a few interesting gems like the following within the first 30 pages.

On where the term corned beef came from:

… Originally “corn” was a generic English word for any kind of grain, even a grain of salt – hence “corned beef”. …

On where the term corn hole came from:

… the shelled cobs were burned for heat and stacked by the privy as a rough substitute for toilet paper. (Hence the American slang term “corn hole.”)

Eventually Pollan converts to a very serious tone when discussing corn. The “corniness” of his family’s meal from McDonald’s is probably higher than you think.

Some time later I found another way to to calculate just how much corn we had eaten that day. I asked Todd Dawson, a biologist at Berkeley, to run a McDonald’s meal through his mass spectrometer and calculate how much of the carbon in it came originally from a corn plant. … soda (100 percent corn), milk shake (78 percent), salad dressing (65 percent), chicken nuggets (56 percent), cheeseburger (52 percent), and French fries (28 percent). …

I never thought of corn this way. Even if you don’t agree or trust his facts (and he recites a ton of data), this book will make you think of corn differently. You will make the link between fossil fuels and corn production, between government subsidies and corn production, between obesity and corn production, and between the environment and corn production. Links that may be debated as to their direct or indirect effect on the well-being of humanity, but thought-provoking and worthy of consideration nonetheless. He sums the corn/industrial section up with:

… America’s corn-fed food chain looks like an unalloyed disaster. I mentioned earlier that all life on earth can be viewed as a competition for the energy captured by plants and stored as carbohydrates, energy we measure in calories. There is a limit to how many of those calories the world’s arable land can produce in a year, and an industrial meal of meat and processed food consumes – and wastes – an unconscionable amount of that energy. To eat corn directly (as Mexicans and many Africans do), is to consume all the energy in that corn, but when you feed that corn to a steer or a chicken, 90% of its energy is lost – to bones or feathers or fur, to living and metabolizing as a steer or chicken. This is why vegetarians advocate eating “low on the food chain”; every step in the food chain reduces the amount of energy by a factor of ten, which is why in any food system there are only a fraction as many predators as there are prey. But processing food also burns energy. What this means is that the amount of food energy lost in the making of something like a Chicken McNugget could feed a great many more children that just mine. …

The thing is, despite his tone, I don’t expect him to give up McDonald’s, especially since his son likes it. He left me with the impression that he’s open-minded about it all; that if his kid says “hey dad, let’s get a McNugget meal,” Pollan would grab a salad and maybe even a small order of fries, and think nothing of it.

Corn falls by the wayside, but the term industrial hangs around for the next quarter of the book because Pollan uses it as a modifier for his organic meal. He unearths a fair amount of hypocrisy occurring in our country’s recent obsession with organic and discusses the facts and perceptions around the term. Here is a synopsis:

And yet, and yet…an industrial organic meal such as mine does leave deep footprints on our world. The lot of the workers who harvested the vegetables and gathered up Rosie for slaughter is not appreciably different from that of those on non-organic factory farms. The chickens lived only marginally better lives than their conventional counterparts; in the end a CAFO [Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation] is a CAFO, whether the food served in it is organic or not. As for the cows that produced the milk in our ice cream, they may well have spent time outdoors in an actual pasture…, but the organic label guarantees no such thing. And while the organic farms I visited don’t receive direct government payments, they do receive other subsidies from taxpayers, notably subsidized water and electricity in California. …

But perhaps most discouraging of all, my industrial organic meal is nearly as drenched in fossil fuel as its conventional counterpart. Asparagus traveling in a 747 from Argentina; blackberries trucked up from Mexico; a salad chilled to thirty-six degrees from the moment it was picked in Arizona…to the moment I walk it out the doors of my Whole Foods. …

… And so, today, the organic food industry finds itself in a most unexpected, uncomfortable, and, yes unsustainable position: floating on a sinking sea of petroleum.

He spends more time on this topic and weighs the pros and cons of going organic, industrial, or industrial organic. This gets kind of tiresome and circuitous, but makes a lot of sense when he moves on to the next meal; the grass fed meal based on ingredients from Joel Salatin’s Polyface Farm in Virginia.

Pollan had heard about Polyface Farm in his research so he called up Salatin and requested to purchase a steak and have it Fedexed to Pollan’s home. Salatin said no, because Fedexing a steak was explicitly against his code of ethics. Salatin says:

“Just because we can ship organic lettuce from the Salinas Valley, or organic cut flowers from Peru, doesn’t mean we should do it, not if we’re really serious about energy and seasonality and bioregionalism.

The interesting thing is that Salatin’s Polyface Farm makes no claims about being organic and Salatin actually detests the word.

… Polyface Farm is technically not and organic farm, though by any standard it is more “sustainable” than virtually any organic farm. Its example forces you to think a lot harder about what these words – sustainable, organic, natural – really mean.

Thus we embark upon what I think is the most fascinating part of this book: the stories of Pollan’s time on Polyface Farm. This Salatin guy refers to himself as an “alternative farmer” or as a “grass farmer.” He basically uses the ecosystem on his farm to maximize his use of the land. Here is a passage that I think is important:

It isn’t hard to see why there isn’t much institutional support for the sort of low-capital, thought-intensive farming that Joe Salatin practices: He buys next to nothing. When a livestock farmer is allowed to “practice complexity” – to choreograph the symbiosis of several different animals, each of which has been allowed to behave and eat as it evolved to – he will find he has little need for machinery, fertilizer, and, most strikingly, chemicals. He finds that he has no sanitation problem or any of the diseases that result from raising a single animal in a crowded monoculture and then feeding it things it wasn’t designed to eat. This is perhaps the greatest efficiency of a farm treated as a biological system: health.

One the coolest examples is the way they have the chickens graze on the same area that cattle have after a three or four day lag. Salatin says “…you’ll always find birds following herbivores…that’s a symbiotic relationship we’re trying to imitate.” Pollan elaborates:

… It seems the chickens eschew fresh manure, so he waits three or four days before bringing them in – but not a day longer. That’s because the fly larvae in the manure are on a four-day cycle, he explained. “Three days is ideal. That gives the grubs a chance to fatten up nicely, the way the hens like them, but not quite long enough to hatch into flies.” The result is prodigious amounts of protein for the hens, the insects supplying as much as a third of their total diet – and making their eggs unusually rich and tasty. By means of this simple little management trick, Joel is able to use his cattle’s waste to “grow” large quantities of high-protein chicken feed for free; he says this trims his cost of producing eggs by twenty-five cents per dozen. … The cows further oblige the chickens by shearing the grass; chickens can’t navigate in grass more than about six inches tall.

Incredible isn’t it? I thought this was so cool, but it’s only one of the tasty morsels Pollan serves up in the Polyface Farm section. I’ll let you read it because we have to get to the meal that he hunts and forages for himself.

This hunting and foraging starts out with Pollan talking about our omniverousness, how being omniverous effects our physiology and psychology, and just how messed-up our dietary habits are in America. He then branches off into the ethics of eating meat. All great, thought-provoking stuff. I have so many pages turned over for stuff I want to talk about that it’s overwhelming, so I’m not going to talk about it.

Anyway, it’s all just a build-up for his trip into the woods to hunt and kill the wild pig for dinner. Pollan, who is somewhat of a vegetarian, is surprised by his trip into the forest to hunt the pig. I love this passage describing the start of the hunt.

Walking with a loaded rifle in an unfamiliar forest bristling with the signs of your prey is thrilling. It embarrasses me to write that, but it is true. I am not by nature much of a noticer, yet here, now, my attention to everything around me, and deafness to everything else, is complete. Nothing in my experience (with the possible exception of certain intoxicants) has prepared me for the quality of this attention. I notice how the day’s first breezes comb the needles in the pines, producing a sotto voce whistle and an undulation in the pattern of light and shadow tattooing the tree trunks and the ground. I notice the specific density of the air. But this is not a passive or aesthetic attention; it is a hungry attention, reaching out into its surroundings like fingers, like nerves. My eyes venture deep into thickets my body could never penetrate, picking their way among the tangled branches, sliding over rocks and around stumps to bring back the slenderest hint of movement. In the places too deeply shadowed to admit my eyes my ears roam at will, retuning with a the report of a branch cracking at the bottom of a ravine, or the snuffling of a …wait: What was that? Just a bird. Everything is amplified. Even my skin is alert, so that when the shadow launched by the sudden ascent of a turkey vulture passes overhead I swear I can feel the temperature momentarily fall. I am the alert man.

Eloquent, intense, and I can completely relate. Not because I hunt, because I don’t. But I play golf, which is stalking a different type of beast. You know what I mean if you’re passionate about golf.

He finally gets his pig. Pollan describes the fourth meal in great detail, the Perfect Meal. It is a great finish to a great book.

Stuff White People Like

I’m pretty much just a white, Euro-mutt. I guess I have a little Greek blood in me, and certainly some German, and also some English and Belgian; but I don’t identify with any of those cultures. I really don’t have any ethnic underpinning. I’m just a white person, basically, and I always figured that I blended in to the American melting pot enough that the quirks of my existence went unnoticed by the rest of society. And certainly, I never expected those very same quirks to be exposed as part of my racial make-up.

But earlier this year, someone brought to my attention the fact that white guys, strangely enough, seem to be the only people wearing shorts with a sweatshirt during those cold days in the shoulder seasons. You know those days; it’s about 50 degrees and you can get away with shorts, but you have to wear long sleeves on top and maybe even a vest because different parts of your body have different tolerances to the cold. Right? You with me? Who doesn’t do that? I mean, it’s just more comfortable wearing shorts despite the cold, isn’t it?

Well, evidently not. This strange clothing regimen seems to be part of stuff white people like and serves to further define my race. Oh, you think I’m crazy, well check out #86 of stuff white people like. There are studies, and there may be empirical evidence. This Lander fellow has done exhaustive research on white people and engages in an ongoing dialogue on the web and in print to document the white race and the unique tastes of millions.

And it’s absolutely hilarious!

I have a warped, dark sense of humor and I understand that this humor is not for everybody. So no, I don’t blame you Mr. White Person if you don’t like it. However, if your dislike is rooted in the fact that you squirm when Lander makes fun of certain shallow and intolerable traits that you exhibit, that probably means you’re just a little too insecure for me. Let me tick off some of the ones that I found pretty hilarious.

Have you ever met that white dude that always tells you that “Guinness just tastes better in a pub in Irelend.” Listen, I drink Guinness, it’s my beer of choice. But I’ve never been to Ireland and I’ve never consumed it in a “real Irish pub.” I’m not lying, about twenty @s#holes over the last few decades have said those very words to me while I’m drinking a Guinness. “Oh Steffen,” they say, “if you think that’s good, you need to go to Ireland to really taste Guinness.” The next time someone says that to me, I’m going to tell them to shut the f&^% up. Hey, I’m insecure, no doubt about it. The fact that some of my best Guinness experiences involve a can, a couch, and college football, makes me feel inferior to those world travelers who’ve been lucky enough to sip the fine beer in Ireland. Hey European traveler, you win, you are a better white person than me.

And what about that whole thing about making you feel bad about NOT going outside? Why do white people do that. I remember my mom saying “hey kids, stop playing Space Invaders and go outside, it’s beautiful out.” To this day, I can’t sit around all day on Saturday watching college football without feeling a huge sense of guilt. Dammit, I’m outside all the time; I play lots of golf and I walk freakin’ everywhere. I’m done feeling guilty about assuming the horizontal position all day on Saturday during September through November. This has been exposed as one of those destructive cultural traits of my race and I’m not going to let it lead me down the road to therapy.

I’m guessing that in Lander’s white continuum, I’m about a middle-of-the-pack white guy. According to him, at one end of the spectrum are people like Eminem and Bruce Willis, who have very few traits generally associated with white people. At the other end of the spectrum, you have the ultra white people like Sean Penn and Ira Glass, who probably read the Sunday New York Times every week, drink a lot of FAIR TRADE coffee, and shop at farmer’s markets. I don’t engage in those, but I do have a Mac, I like hummus, I wear a fair amount of outdoor performance clothes, and I’ve been promising to learn Spanish for years. So yeah, there’s no mistaking the fact, I’m white, but you may have to ask some detailed questions to figure out if I’m the “wrong kind of white person” (someone who, for example, feels that their gym teacher was their favorite high school teacher).

I guarantee that Lander will rip something that you cherish. He won’t just rip it, he will expose it, analyze it, throw it on the ground, spit on it, then walk away; and you will have no recourse. He has no mercy. You go through stages during Landers’ satirical trashing.

- First you’re angry that someone could make fun of something that you hold so dear.

- Then, you feel like an ass because he starts making sense and you actually start to understand the hypocrisy that he is exposing.

- Finally, you see the humor in it all, and you laugh. In fact, you may even change your behavior a little.

This is a great book for the audio format. It’s brainless and the narrator has a great, deadpan, documentary-style delivery. I laugh a lot when I think about it and I think it’s really creative stuff.

The Last Colony

This is my one sci-fi book for the year. That’s one horror and one sci-fi in 2008, which is about normal for me. This is the third, and last, in the Old Man’s War trilogy by Scalzi. I read the first one back in February 2007 and they’ve all been great. I read this one the fastest. In fact, despite being pretty busy, I think I banged this thing out in about 3 days. The only book I can recall reading faster was The Kite Runner.

If I were to rank the books in this trilogy them by coolness, I would go 1, 3, 2. If I were to rank them by how thought provoking they were, I would go 3, 2, 1. On pure action, I’m saying 1, 3, 2. On chances for a great movie, this is the one. I’m reading a few heavy books right now which will get posted between now and the end of the year, so I needed this break from reality.

This book brings together the main character of book one, John Perry, and the main character of book two, Jane Sagan. They are married and living a somewhat genetically unmodified life, with their adopted daughter, on a quiet planet somewhere in another solar system. Then they get an offer from the governing body of the human universe (the Colonial Union) to be the leaders of a new human colony on another planet. It seems like an exciting opportunity to them, so they accept it. There are a couple of curveballs for the couple. First, the mortal enemy of the humans, this group called the Conclave, will stop at nothing to destroy this colony. Second, the Colonial Union may not really care if everyone in the new colony dies and is not above putting the new colony in harm’s way to further their own political agenda.

It’s a good combination of military and politics. Scalzi certainly draws up some intense and creative battle scenes, but the political discussions and verbal sparring are the highlights of this book. The dialogue is complicated and multi-faceted, yet very clear and easy to follow. It centers on a general mistrust of the government’s truthfulness (or lack thereof) with its subjects.

The ending is really cool and wraps up the trilogy (at least according to his credits). But I think he has already incorporated characters in a new book so maybe it will be kept alive forever. If I really wanted to get the story, I could probably just go to Scalzi’s website and read some of his ruminations. Like no other author I know of, his life is really an open book. I used to be more of an avid reader of his blog. I no longer subsribe to his blog feed but I do go there every so often to see what’s up. Check it out. I would love it if more authors did this sort of internet marketing.

Little Red Book of Sales Answers

Yes, this is basically a self-help book. But it’s a business self-help book. Business because it focuses mostly on stuff you can do to grow your business and increase your sales. Self-help because it focuses on developing personal skills that will help you in sales rather than the strategy and tactics of closing the deal.

Articles of War

I got this book in Denver, CO. It’s a great town and the Tattered Cover is a great, independent bookstore. It was displayed prominently at the entrance because it was the “One Book, One Denver” offering at the time. Arvin is a Denver resident with roots in the Midwest (he went to U of M). I’m a damn fool for some local flavor so I grabbed it.

This is a story about the horrors of war; World War II in fact. It’s about a fictional kid named George Tilson who lands in France and makes his way across many battlefields dodging German bombs and bullets. Early on, he doesn’t separate himself as a proficient fighter and barely fires a shot. He spends most of his time beating himself up for being afraid.

There was good reason to be afraid. Large chunks of the book are devoted to describing just how awful it is be in battle. He spends his time in dirty foxholes and is always on the brink of starvation. He sees fellow soldiers get shot, blown up by booby traps, and killed by freak mishaps. There is some hope. In the background and often on his mind is a woman he met during his first week in France. Here name is Claire.

** PLOT KILLERS FOLLOW **

On the violent front, his desire to leave the battleground and find Claire is so great that he raises his hand above the cover of a brick wall hoping to get shot and thus get a ticket out of the war. He takes a flesh wound but it’s not enough to get him sent home. Even worse, shortly thereafter he gets chosen to participate on a firing squad chartered to execute a deserter named Private Eddie Slovik.

The picture of Eddie Slovik struggling to stand after being shot by the firing squad haunts Tilson for the rest of the war. I think it basically desensitizes him to everything in life. This allows him to finish out the war as a respectable fighter and he even volunteers to hang around after the war to help rebuild. He is so desensitized that he even ignores Claire after noticing her in a line of beggars holding a baby. He finds out shortly after from Claire’s father that she was raped by a Nazi.

The last scene finds Tilson in the bunkhouse when he hears a knock at the door. He opens the door but nobody is there. Then he hears the crying of a baby. It’s Claire’s baby girl and note requesting that Tilson take care of her.

The book ends there, leaving the open ended question of whether Tilson has the emotional fortitude take the child in. I’d like to think that he did so and that it changed his outlook for the rest of his life.

Arvin’s inspiration for this book appears to have come from another book called The Execution of Private Slovik. According to the book, Private Slovik was the only deserter during the war to pay the ultimate price of death. It was even made into a movie with Martin Sheen. Check out some of the reviews on Amazon of the movie, it seems to have stoked some passions.

It’s not light reading. I may have to get the movie.

Match Made in Heaven

Yes, I play golf. A fair amount of golf in fact. Here is my golf cred. What kind of idiot takes pictures of every one of their scorecards? Well, me. And inevitably, I read a few golf books each year. This is a fantastical piece of golf fiction about a dying man whom God gives one last chance to live; all he has to do is beat a group of historical figures in an eighteen hole match on the course on which he learned the game.

The main character is Elliot Goodman; athlete, professor, husband, father. He just had a heart attack and is being driven to the hospital when God makes a visit and strikes the bargain. Goodman plays eighteen imaginary one-hole matches and has eighteen imaginary conversations with dead people. Certainly, these are dead people who Mitchell holds in the highest regard. Fun stuff.

** PLOT KILLERS FOLLOW **

Goodman’s opponents range from DaVinci on the first hole to an old golf club employee near the end. He plays against singers, athletes, movie stars, and other various historical figures. It appears that Mitchell is passionate about the game because he exhibits a fair amount of knowledge of golf. But don’t read this book for insights into match play strategy; read this book to get in touch with the mystical nature and simple pleasures of the game.

For example, here is why John Lennon plays golf:

“… I mean, some people play golf ‘cuz they wanna see how low they can shoot? And some play ‘cuz they’re outgoing and competitive? Me? I couldn’t give a shit about the scoring. I play ‘cuz it’s fun!

Hitting the ball from one spot to the next and just being outdoors, ya’ know? And feeling free and looking at the trees and the grass and the birds and the clouds. …”

I like this take. Lennon was his opponent on the fourth hole, so there is plenty more golf love to come.

While playing Babe Zaharias, Goodman makes this observation:

He had often thought that golf is a particularly glorious game, not just for all the obvious reasons, but for one in particular. Of all the major sports, it is the only one where, if you’re “in the zone,” you can perform, at any given moment, on any given day, just as well as, and probably better than, anyone on the face of the earth who ever played the game!

Not a bad take. Sure, a weekend warrior like myself, even in the zone, can’t compete with the pros. But there are those tiny moments, those great holes, those flushed shots, that allow you to do something great that can’t really be bettered by any other human. Heck, I dropped a flushed six iron into the hole on the first at White Deer Run about five years ago for an eagle; that shot couldn’t have been hit any better by Jack or Tiger. Contrast this to my marathon experience, where I was running the same course as the world class athletes, but never once could I feel remotely comparable to them. I was logging 8:50 miles and they were logging 5:00 minute miles. I couldn’t fathom running that fast. Heck, that’s an all out sprint as far as I’m concerned and they are doing it for 26 miles. Insanity.

Goodman also makes some keen insights sports in general. I’ve always been a big fan of being a balanced athlete. I think Tiger’s greatness is locked up in his balanced approach to the game. He has every angle covered; the mental game, the emotional game, fitness, distance, touch around the greens, clutch putting, determination, accuracy with the irons. He practices the range of skills needed to succeed and never focuses on a single aspect, he has no weaknesses, there are no chinks in his armor (although it could be too much too fast given this knee injury, we’ll see). Mitchell, through Goodman, makes a similar point about Willie Mays:

Willie may not have been the pure hitter Ted Williams was or the power hitter Hank Aaron was or have had the early Mickey Mantle’s speed afoot, yet he was greater than them all in his peerless brilliance in all aspects of the game, his unparalleled charisma, and his boundless and profound passion for playing baseball.

Tiger may not have the charisma of Willie Mays, but he defines “peerless brilliance in all aspects of the game.”

Then Mitchell pulls off a gem like this, right from the mouth of William Shakespeare:

O golf! Thou dost imbue mine life with meaning

And givest me a purpose to trudge on!

Thou showest me mine frailties today,

Then showest me anew, quite on the morrow,

And makest me relate to mine own flaws

And human peccadilloes of mine doing;

Just as I revealed in others’ lives

The sins and imperfections of a Man,

So hast thou shown in me that vanity,

That greed, that lust for pow’r, that blind ambition,

That madness born of rage, that indecision,

That green-eyed monster envy, which inhabit

Yet every pore and wrinkle of my being!

There are a lot of messages in those lines. The Shakespeare match, written in the form of a play, is pretty cool. I’m not exactly sure if it was in iambic pentameter, but it was very cool nonetheless.

In keeping with Mitchell’s high regard for balance, after beating Babe Ruth on the fifteenth, Goodman makes this observation about his stellar play and how it reflects his own life:

The Babe, impressive as he was, was a one-trick pony out there. Power, power, and more power. And me? Not much to talk about for the macho guys in the locker room, but I sure got the job done. Come to think of it, I was the model versatility out there! Power, in moderation, on the drive, intelligence by choosing a safe three-iron on the second shot, the finesse to keep it on the top tier with the pitch, and accuracy with the putt. The complete package!

Elliot thought about how lucky he had been to be versatile and multifaceted during his life, too. About how he could do and be lots of things, using various talents and energies and fields of expertise, and have lots of passions and play different roles in dealing with different people.

He was fortunate not to be a Georgie One-Note.

This kind of careful thought about the game gets a little deeper in the match with Gandhi. Gandhi goes on a long diatribe about why he loves the game so much:

“… You see, my good friend, the game of golf is the epitome of the essence of satyagraha. That is why I love this game so exceedingly much. Because in golf, as in life, there is much to be learned from truth in firmness, from nonviolent resistance.

In both golf and life, there is strength through gentleness. There is results through patience. There is moving forward through yielding. There is achievement through self-restraint. There is fruitfulness through abstinence, gain through compromise, victory through humility, reward through sacrifice.

… It is about complete service to the game…”

This is a solid, thoughtful, golf story. It didn’t rock my socks off while I was reading it, but it did make me reflect a fair amount about my love for the game. That’s important for golf fiction, it needs to constantly make you reflect on the game and your relationship with it. If you play the game, I think you’ll like this book.

The Essential Drucker

My familiarity with Drucker is mostly from reading certain excerpts of his stuff as an undergrad. I regret not “getting” the management classes I took in school. I liked pouring through the detailed concepts of finance, economics, and accounting but I didn’t expend the same amount of resources on management. In retrospect, this stunted my development as a businessperson. There is a certain aspect of thinking from the organizational and personal development level that I didn’t do until my mid-30s.

Maybe it’s a function of age, but now management books are really interesting to me. This book is especially interesting because of its scope and efficiency. It distills a big chunk of Drucker’s management theory into a well-organized and relatively short book. The subtitle is “The Best of Sixty Years of Peter Drucker’s Essential Writings on Management.” It’s the management book you read before you read other books on management; actually, before you read another business book period.

The first chapter sets management in the intellectual realm. Drucker first describes the task of management with a caveat (page 4):

To be sure, the fundamental task of management remains the same: to make people capable of joint performance through common goals, common values, the right structure, and the training and development they need to perform and to respond to change. But the very meaning of this task has changed, if only because the performance of management has converted the workforce from one composed of largely unskilled laborers to one of highly educated knowledge workers.

He then proceeds to broaden the scope of the term management (which I wish I would have read in 1987) and eventually describes management as a liberal art.

Management is thus what tradition used to call a liberal art – “liberal” because it deals with the fundamentals of knowledge, self-knowledge, wisdom, and leadership: “art” because it is also concerned with practice and application.

I agree with Drucker, management is worthy of focus. It doesn’t come naturally except for the gifted few and you will be better positioned to help yourself, your business, and society if you at least have a rudimentary understanding of what it’s all about.

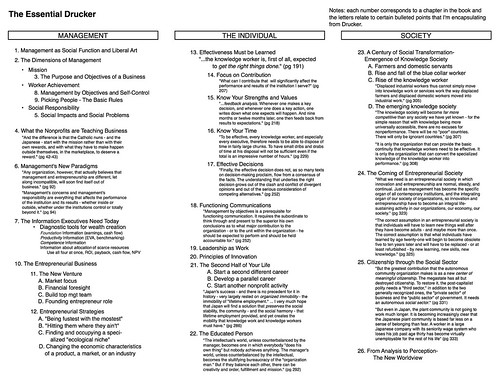

There is so much in this book that to begin pulling out the gems is difficult. The easiest way for me too depict it is with a cheat sheet of some sort. Check it out below. There are 26 chapters and they are grouped into Management, The Individual, and Society. I’ve taken things a few steps further and sub-grouped the chapters to assist the reader. I’ve also highlighted a few quotes and lists that I think represent the point of each chapter.

It’s very theoretical and very fascinating. Drucker is a national hero in Japan (reminds me of Ben Franklin and his stature in France) and he clearly has great fondness and high hopes for the country. Applying his experience from that country to the US and management in general is a keen aspect of many of Drucker’s writings.

I highly recommend this book just to have around. You don’t need to read it all in one sitting. If you are in a reflective mood around your annual performance review, read chapters 13-17. If you are thinking of starting a new business, read chapters 10-12. In either case, Drucker will satisfy your needs or provide a basis for digging deeper into the topic.